This week ERA is exploring the history and design of storefront architecture. To understand the origins, evolution, and future of this iconic feature of commercial buildings, ERA writer-researcher Alessandro Tersigni sat down with Shannon Clayton, the firm’s resident storefront expert.

Shannon has worked on many conservation projects involving the design of new storefronts for commercial heritage buildings in Toronto, including 1 Yorkville and the IMMIX tower at 480 Yonge Street. Her research tracks the ways in which technology, economy, and design values gave rise to storefronts and examines the factors that have led to their decline in North American contemporary architecture.

Alessandro Tersigni: Storefronts strike me as one of the fundamental urban building blocks. Do you think North American cities could exist without them?

Shannon Clayton: Storefronts aren’t unique to cities—they’ve been at the core of most commercial architecture, regardless of location. There are so many small towns that have amazing storefronts. For example, Picton in Prince Edward County has beautiful storefronts, many of which are more intact than those in Toronto, because there has been less turnover and development pressure. The aesthetics of a storefront have more to do with its construction date than the size of a municipality.

AT: Take me through the evolution of storefronts as we think of them today. What did that architecture look like, say, 1000 years ago?

SC: In the ancient world, there was no barrier between exterior and shop. Commerce happened in open-air marketplaces, which of course still exist today in warm climates and temporary events like farmer’s markets. Over time, stores increasingly became physically separated from the street to manage climate and protect merchandise. In the medieval and early industrial eras, there wasn’t much of an architectural distinction between ground floor stores and residential spaces above them. It’s not until the Georgian period that storefronts emerge as a larger glazed wall area that’s distinct from a window and intended to reveal the businesses within.

AT: How have technological innovations shaped storefronts?

SC: Glassmaking and frame technologies have had an enormous impact on the aesthetics of storefronts. Georgian storefronts in England usually featured many relatively small panes of glass. At the time, glass was made by the Crown Process, which involved spinning blown glass into a circle until flat and dividing the surface into limited panel sizes. The Victorians developed the cylinder drawn method of glassmaking, which allowed them to create the larger pieces of glass that you see in historic storefronts across Ontario today. I would argue that the most critical technological turning point in the evolution of storefront design was Francis Plym inventing resilient sheet metal sashes in 1906, and subsequently founding the company Kawneer. This was the first time that glass could be held in place without wood or putty. Instead, a sheet metal component was secured in tension to support the glass. After that, storefronts rapidly transformed from a custom design exercise to an increasingly standardized product.

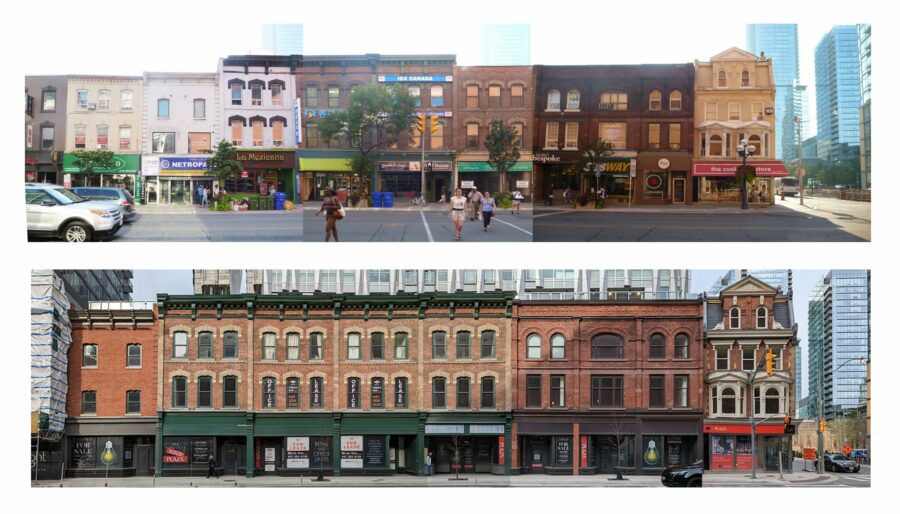

AT: Is there anything about Toronto’s historic storefronts in particular that’s unique?

SC: Something I’ve noticed is that the city’s Victorian storefronts, which are present in a large percentage of its building stock on commercial roads, are predominantly wooden. Many American cities of comparable sizes had thriving steel trades in the 19th century and are full of early metal storefronts — think of SoHo’s iconic cast iron windows in New York City. Perhaps Toronto’s abundance of lumber and skilled woodworkers led us in another direction.

AT: What’s going on with storefronts in the 21st century? Are we still building them?

SC: I would say no. That’s the question that spurred my research on storefronts in the first place: Where did they go? My theory is that storefront framing technology eventually paved the way for the glazed wall systems that are now omnipresent in North America’s condo architecture. Glazed walls have entirely superseded and absorbed storefronts as an entity separate and distinct from the rest of a building.

The problem is that the base of the façade has become the most generic part of new buildings, but it has the greatest impact on the urban experience. There used to be this hierarchy of building design in which the most detailed elements were on the ground floor because that’s where people have the most interaction with the architecture. Today, street-level design is so optimized that it’s become an afterthought.

AT: Do you think the advent of online commerce had anything to do with that paradigm shift?

SC: I don’t think it necessarily had much to do with the internet. Yes, smaller businesses are turning to e-commerce, partially because of rising rent costs of commercial spaces. But I think development pressure is a bigger driver of that transformation. Say I’m working on a project incorporating historic storefront façades into a new condo tower — the developer will usually want to attract an anchor commercial tenant they can count on for rent, typically a big chain like Shoppers Drug Mart or a bank. To do that, they prefer to design for the largest possible ground floor spaces, rather than the fine-grain storefront breakdown that’s historically been emblematic of urban centres. That can have a really significant impact on the rhythm and variety of the street.

AT: Based on your extensive work rehabilitating storefronts at ERA, what do you think drives this practice? Is it a matter of honouring historical forms, implementing good urban design, or satisfying our aesthetic tastes?

SC: That’s a really good question. Things like human scale, rhythm, proportion, and visual interest are not necessarily stylistic or historical — they’re based on a human walking through a space. That’s not going to go away. You can absolutely interpret those characteristics in a contemporary language with modern materials. A successful storefront doesn’t need to have wood pilasters. It’s just about a respect for how people naturally engage with buildings.