My interest in the redevelopment of Honest Ed’s and the surrounding neighbourhood is informed by my work in placemaking and stakeholder engagement — and also childhood memories. Prior to becoming a senior healthcare professional, my single mom worked at a series of low-income jobs. She moved in and out of our tiny apartment like a streak of light in an unfocused photograph. Sometimes she slowed down long enough to take me on an excursion to Honest Ed’s.

I loved everything about the store. The vibrant lights. The way my mom looked at me in delight when I read the hand-painted signs aloud. The way children could run about and speak using our outside voices unlike those fancy shops.

Although I was young, I knew my mother struggled to support my sister and I. Yet she happily filled our cart with canned fish, laundry detergent and sweets, which she later shipped to relatives in the Caribbean. Having immigrated to Canada at four years old, I had no memory of these relatives but I sensed that this ritual was an important one for my mother. Upon learning about the redevelopment of the site, I reflected on this experience and it dawned on me that Honest Ed’s is one of the places where I was taught accountability and giving. Although this part of my personal narrative holds significance for me, it’s not particularly unique. Almost every Torontonian has a special Honest Ed’s story.

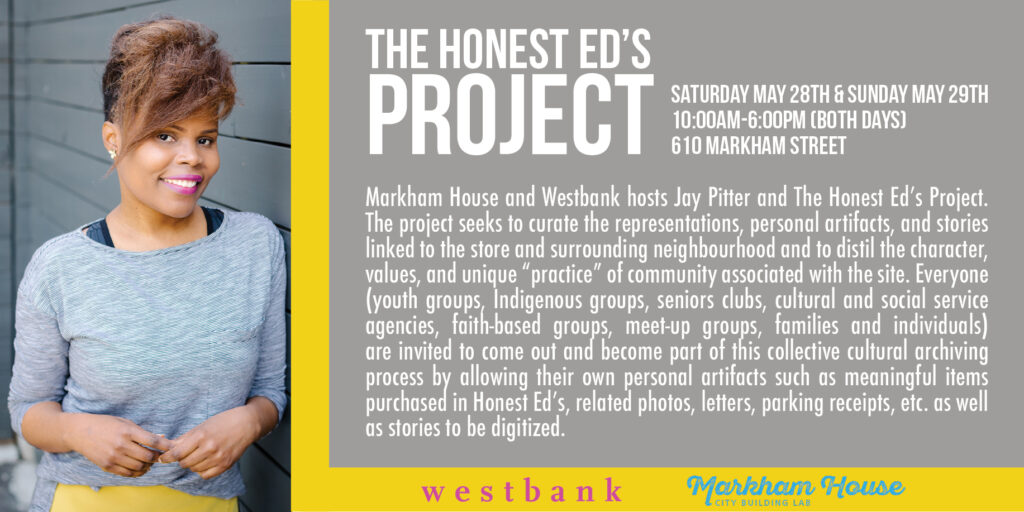

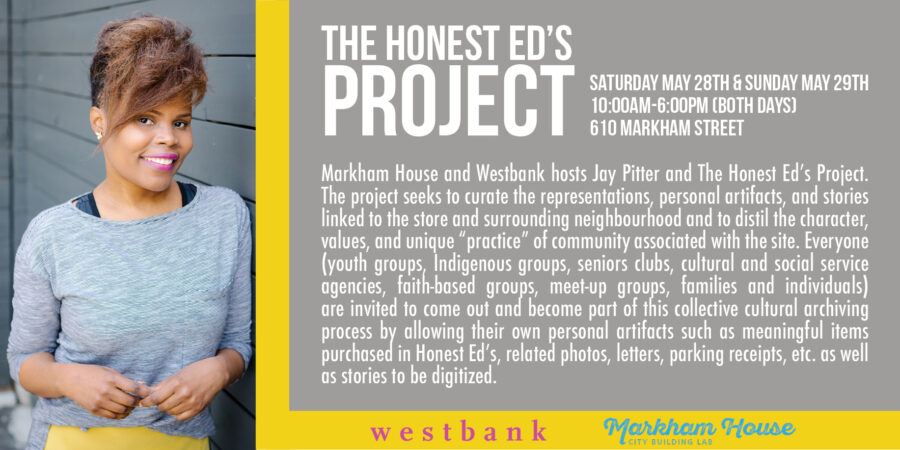

Stories are a good way to think through rapidly changing urban neighbourhoods. Local mythology, memory and shared values are as consequential to shaping inclusive and vibrant communities as the height and siting of buildings, greenspace and accessibility. Increasingly, intangible heritage approaches are incorporating strategic storytelling components. Specifically, I sought to initiate an intangible heritage project that would incorporate the voices of stakeholders often excluded from official local history and urban development processes; not as an act of conservation but as a form of “community practice” and meaningful engagement.

My idea was a simple one. I enlisted a photographer and a couple of volunteers. Together we would stand on the corner of Honest Ed’s from 2:30p.m. – 2:30a.m. and ask strangers to share their Honest Ed’s stories. This timeframe was integral to the process because the character of a place and the people who occupy it transitions throughout the day. A street filled with families seeking organic fruit markets and trendy patios begins to shift at dinner time. When this same group is settling in for an evening of Netflix, hipsters and Hip Hop fans start heading out to entertainment venues. Street-involved activities begin to surface as club DJs begin their sound checks. Later in the night, “invisible” factory and restaurant workers descend from the all-night bus while people without housing start making difficult decisions about their sleeping accommodations. Because I wanted to speak to everyone, it was imperative to brave the twelve hours of standing, sloppy propositions and unrelenting techno beats emanating from local clubs.

And it was worth it. I curated almost one hundred stories. A married couple shared memories of their first date exploring the store. A historian brought me a kitschy tea cup she purchased for her mother as a broke student beaming that it was incorporated into the family’s prized Royal Doulton China collection. A woman living on social assistance shared her fear of losing her affordable healthy food market.

Then I met Martin.

Martin was an elderly man, weathered and slightly suspicious, as individuals who have experienced the world are entitled to be. I answered each of his questions about the project carefully, and at times, felt like I was the one being “interviewed”. When satisfied by my responses, he opened up his wallet. I leaned in, intrigued. He produced a black and white photo of a much younger man. “This is me, the only holocaust survivor in my entire family,” he said.

I forgot to breathe, but he didn’t notice. He was too busy searching for what seemed like rarely spoken words to describe experiences of an unspeakable time. He shared the despair and loneliness of struggling in several Nazi extermination and concentration camps, including the infamous Auschwitz-Birkenau. When the war ended he sought to get far away from its remnants and so he left Hungary for Canada. His first job was working in a mattress factory. “I liked my job and even better I met a beautiful girl,” he beamed.

His hands shook slightly as he produced another photo, of a young woman who could easily pass for a Hollywood starlet. Soon they married and he dared to place enough faith in the world to bring children into it. Sons were born. After work Martin would often go to Honest Ed’s, then called the Honest Ed’s Bargain House, to purchase items for his family. He told me that each time he entered the store he felt a sense of hope. After living through the holocaust he could not believe that a Jewish business owner could be safe and embraced by so many people. And so he kept coming to the store for this powerful, and perhaps healing, reminder.

A lot happened during the over half century that Martin regularly visited Honest Ed’s. The “pretty girl” that helped him to build a new family was lost to cancer. His children moved away. And now, with the store’s redevelopment, he would experience more change. Within the context of global cities like Toronto, change is particularly rapid and complex. Intangible heritage approaches provide us with an opportunity to ensure that we understand the “community practice” of places, ensure that the voices of Indigenous and other historically marginalized communities are heard and honour the experiences of individuals like Martin.

Jay Pitter established a career as a public funder and then a communications and public engagement director before earning a graduate degree at York University’s Faculty of Environmental Studies. Her work is focused on inclusive stakeholder engagement, placemaking and city-building initiatives. She has been a guest lecturer at the University of Toronto and York University, and was recently a faculty member at the University of Guelph-Humber. Her writing credits include Spacing, CBC Radio, the Toronto Star and the Coach House Books anthology Subdivided, which she contributed to and co-edited.