Vincent Massey Tovell passed away in May 2014. He was a talented broadcaster, a remarkable thinker, and a tireless supporter of the arts. In 2006, for the publication Concrete Toronto, ERA conducted an interview with Mr. Tovell on the subject of the modernist architecture of Toronto and the nation. Below we re-present this interview as a modest reminder of his contribution to our understanding of culture and the built environment in Canada.

ERA: The ‘6os marked a big change in Canadian culture – it is always mythologized as Canada coming into its own. What do you see as the big changes?

Vincent Tovell: The ‘60s, of course, are very easy to talk about. There was a kind of dynamism that had not existed. It wasn’t possible during the Depression, and it couldn’t be done during the war. War was static. It was great for industrialization. It was great for building all sorts of things that hadn’t got built before, like tanks. That was the industrial profit of the war; we profited well out of the second war. No doubt about that. Look at the ships, look at the cordites that got built in Collingwood, and all that. But it didn’t affect domestic architecture until we got to the postwar stages. The advances in arts and culture that were starting in the ’20s pretty well stopped for two decades, then shot off with a bang after the war. The ‘60s were really a wonderful period. New ideas were for everyone, not just an elite.

There was a whole new generation of people after the war who travelled, who were open to new ideas. There came a kind of new middle class with the possibility of university education, who had worked in the forces. Men and women. And there were new kinds of families. A great flourishing of Scandinavian furnishing for small apartments, which is where all the young couples had to live. They didn’t inherit great houses to live in; they had to make do. And the great market for the Scandinavian furniture flourished everywhere across the country, and I think it’s beneficial. I have some. Everybody did.

ERA: How did this new cultural attitude express itself in terms of design?

Vincent Tovell: Through very sophisticated architecture. There was the wave of confidence, there’s no doubt about that, prosperity after the war. And I do think it’s terribly important that the architects were one of the beneficiary groups in this. There were talented architects ready to push the old guard out. And they were – you can think of them now in retrospect – the giants of the period. Parkin was a big leader in this, undoubtedly. John had an enormous influence on many people, not just as the modernist, which is how he got labelled most quickly – like Gropius and all the others from Harvard. But he really was eager to break the patterns and change. And he was a force in the world of the emerging Canada Council – getting them to think in new terms. He wasn’t the only one, but he certainly was a leader. The idea of the Bata was one of the great ones for him. He won the National Gallery Competition, if I remember correctly – one of the ones they didn’t build.

And it’s a pity there isn’t more published about John Parkin. He had a tremendous influence in this country.

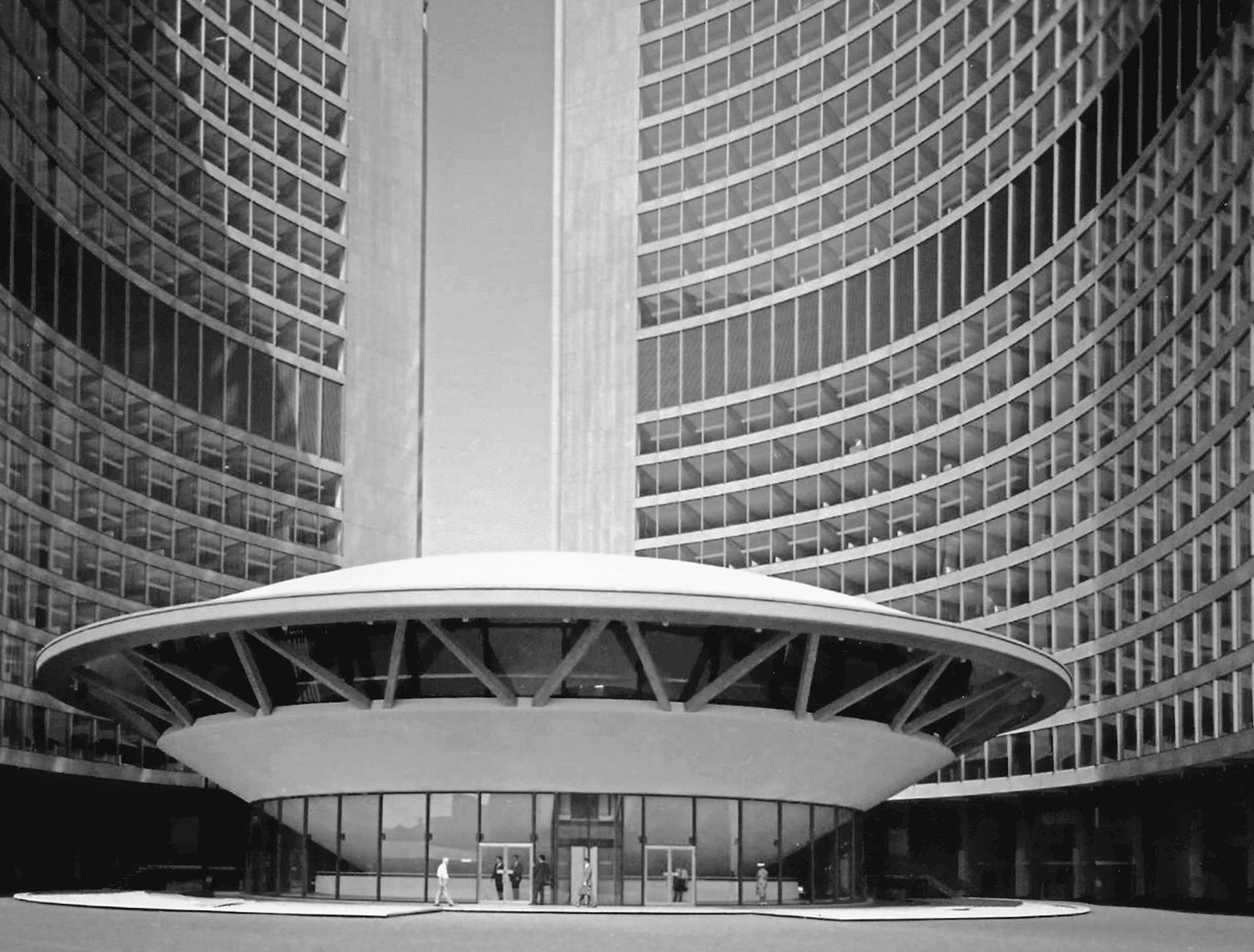

Eric Arthur is another one, in his own way. Based at the University of Toronto, with his interest in not just the historical material, which he shared with Tony Adamson to some extent. He got the students activated to get the new City Hall of Toronto competition going. He really guided that competition. It was a shock for Toronto. They even called Frank Lloyd Wright – I don’t know which of the newspapers did – to get him to say something outrageous. Of course he hadn’t seen anything, but he proceeded to say it anyway. But it was a worldwide story for architecture.

ERA: There was a flood of modern architecture that came forward in the ‘60s. Quite a radical change. What was the public reaction? Did people like these buildings?

Vincent Tovell: They definitely did. I have no hesitation in saying this. People were curious. This was something people here had never seen before. There was sheer curiosity. City Hall, for instance, was a storm, and it was wonderful, because it looked strange. ‘What was this going to be like?’ In retrospect, you’d have to say it was very, very well received early. It was so exciting. And clearing away all of that downtown mess. Regrettably, the old Shea’s Theatre with its old vaudeville shows – I missed that. Not to mention the casino across the way. All those closed. And then the big storm about the Henry Moore sculpture in the plaza. Well, you see, it broke through! It wasn’t just art gallery stuff. It belonged in a public place.

ERA: Is it true that the old architectural guard in Toronto never forgave Eric Arthur for the City Hall competition?

Vincent Tovell: Maybe the public was receptive of new pieces, but I think the old guard was less receptive of new or younger architects. It may be that younger architects had a hard time breaking into the successful contracts, but that didn’t last long – it became a wide-open game. Something got lost, however, because the old guard had skills. They also had styles they were masters of. You couldn’t build a building like the Medical Arts Building today. I don’t suppose any of the young architects would have any idea how to go about thinking that way. It was all about innovating – but when you’re always innovating, do you know how to detail that?

ERA: And how did people react to characters like Peter Dickinson and Mies van der Rohe? What was the idea of architecture as a personality?

Vincent Tovell: Peter Dickinson was a great success, wasn’t he? Benvenuto, which is still his place, that was successful at every level, wasn’t it? People liked it. And it worked in business/commercial terms. And there was the O’Keefe Centre and the towers at Regent Park. I don’t remember hearing of him as particularly controversial. He was certainly ‘of the times.’ And he seemed to understand what could be done and got them built, and of course he was so young when he died, wasn’t he?

ERA: Thirty-six …

Vincent Tovell: And that was a shock. Because he was a leader, obviously. I’m not sure that Mies represented any great disturbing aesthetic. It looked so practical for a start. And then an awful lot of the business people, the money people – the big money – liked that building because they looked as important as they would in Chicago or New York or somewhere they really would fit. I had friends who were young lawyers working in that part of the new Canada, the big corporate structure that was evolving, and they were very proud to be around there: We’re big-time now.

When you think of the sheer scale of the projects through the progress of the ‘60s, you can see the really interesting trends emerging and you can make your own lists of the architects. Think again of John Parkin, of course, and Ray Moriyama … and the list goes on.

ERA: Was there the notion of architect as celebrity as there is today?

Vincent Tovell: Not like today. But John Andrews was a real showman. He said to me, ‘Architecture is a performing art. If you can find yourself in the New York Times or the centre spread of Time magazine, then you’ve made it.’ And he accomplished all of the above, the latter with Scarborough College.

ERA: Many of these projects were a radical departure from what people were used to. Was the country generally receptive of international ideas?

Vincent Tovell: Absolutely. This is most evident in Expo. People still prattle on about Expo as the most exciting time they ever spent – because there was money available one way or another to go to Montreal and actually wander around. Some of the Canadian buildings were in themselves landmarks. Real landmarks! Arthur Erickson did one. The federal building was done by Colin Vaughan. And Grossman’s News and Administration building.

The centennial itself was huge. Of course with Expo, but also there were celebrations right across the country. The government decided to put money into it, which all the towns had access to, some provincial, some federal. And all kinds of activities that had never happened before. The celebrations were all about moving forward.

ERA: Expo, the centennial – there seems to be huge investments in all directions. Would you say this time reflects a period of country-building?

Vincent Tovell: Country-building, absolutely right: national libraries, the Canada Council, investment in universities, and on and on. This was all in response to the population exploding, and a new sense of what the government could do. The country was growing at such a rate, and with the mixing of people from all over the world, there was a new kind of public, and a real need for investment.

The ‘60s were the beginning of all the new performing centres. Then in 1967 you had the Ontario Science Centre project. There was no precedent for that, a new centre for learning, with all the public schools rearranging their curriculums to have school trips there.

The whole educational apparatus became much, much bigger, as did the hospitals, as did everything. This era was the laying out of the key infrastructure, which is still today the sacred backbone of most Canadian cities. And the leadership of the governments, especially here in Ontario, encouraged all these things. They kept nurturing it, and this was very necessary.

ERA: Through all of this, do there think there was a developing sense of a Canadian style in the ‘60s?

Vincent Tovell: Well, that’s part of a subtle issue. I think architecturally you can argue yes. Ron Thom, Arthur Erickson certainly, represented something that was particularly western, particularly BC, as we know it. The use of materials, the sense of outdoor/indoor. Whereas you could say the Parkin-Gropius line really was much more related, perhaps, to central Canada, with its climate issues. Opening of glass was very important – gets lots of light – long winters. Certainly there was that. But I don’t know that you could say there’s a unified style right across the country. But everybody was encouraging diversity. I don’t think anybody wanted to impose anything particular. Also, it was not easy to get around in this country; it was expensive to travel. The growth of airlines helped. The growth of television helped enormously.

ERA: You worked as a broadcaster at the CBC, communicating to the nation. You had Revell and John Andrews as features on your show Explorations. Some today might be surprised that Scarborough College’s concrete was a star.

Vincent Tovell: As I said, people were interested in new ideas. We were all learning, including us at the studio. Television was a new way of connecting our vast country, and the CBC took full advantage. Our program was introducing our audience across Canada to any and all interesting bits of arts and culture from around the world – from Japanese temples in Kyoto to Le Corbusier’s concrete La Tourette in France. And of course modern architecture here in Toronto. Most people had previously never seen images of these things, and there was a tremendous excitement about learning. It was all new to us, regardless of what time period it was from. World travel was still expensive, though it was becoming cheaper, but now it was possible to see the world through television. Also, colour photography was just beginning to expand after the war, and it changed our whole way of looking at everything. It’s interesting how much our visual horizon has changed.

ERA: Before we go, any thoughts about concrete?

Vincent Tovell: The use of concrete was partly a practical solution, wasn’t it? The massive growth and the sheer number of buildings that needed to be built – and built quickly, I suppose – demanded concrete, and architects used this to design a new kind of expression. You couldn’t build the old way. Couldn’t get the stonemasons, in fact, is what it boiled down to. You couldn’t afford to pay them. The kind of stone work from Richardson and Lennox, that was another generation, and this was a new type of architecture. It seems like after the City Hall the fashion of the day was the new ideas, the new generation. It became the point at which to go with the old guard would have been a bad move.

They were remarkable times, really worth remembering. And looking back, it was quite something being in the middle of it.